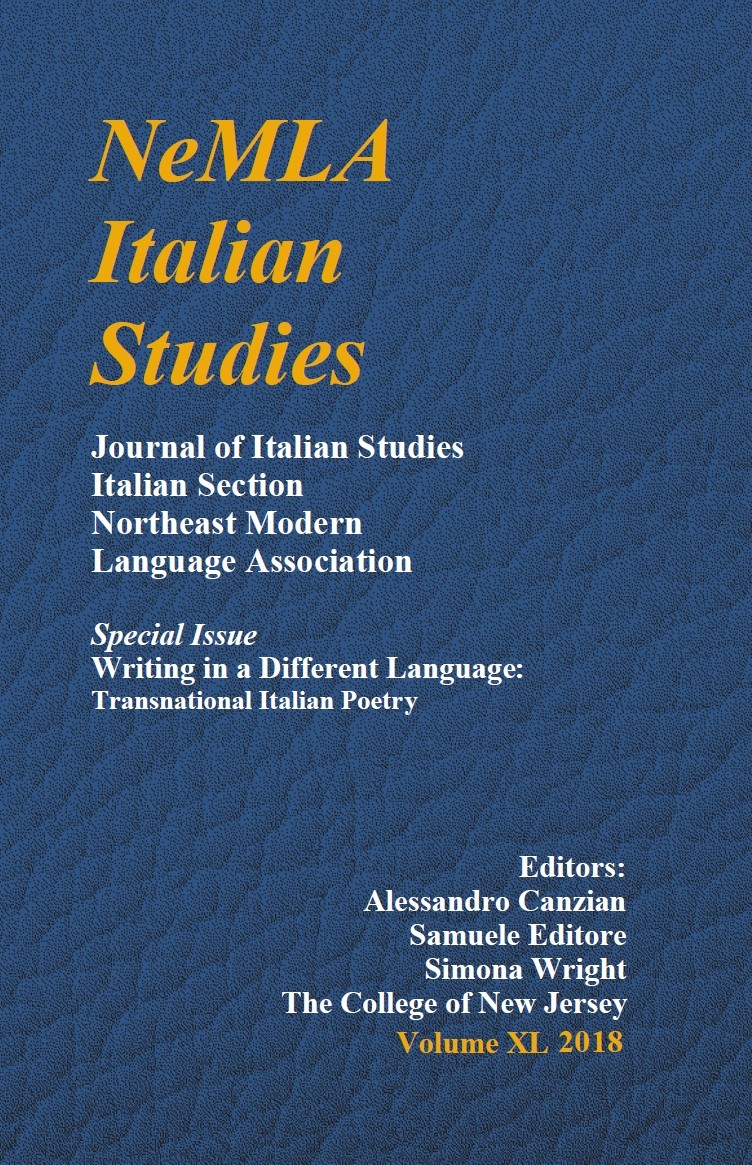

NeMLA

Italian Studies

Journal of Italian Studies

Italian Section

Northeast Modern Language Association

Special Issue:

Writing in a Different Language: Transnational Italian Poetry

Editors:

Alessandro Canzian (Samuele Editore)

Simona Wright (The College of New Jersey)

Volume XL, 2018

CONTENTS

IX

Introduction: Transnational Italian Poetry

ALESSANDRO CANZIAN AND SIMONA WRIGHT

1

Translingual Peripheries: Ilaria Boffa’s Practice of Everyday Poetry

SIMONA WRIGHT

13

Selected Poetry

ILARIA BOFFA

31

A Strange Geometry

VICTOR XAVIER ZAROUR ZARZAR

41

Selected Poetry

MOIRA EGAN

61

The Depths of Love and Sorrow in Allison Grimaldi Donahue’s Poetry

CRISTINA PERISSINOTTO

63

Selected Poetry

ALLISON GRIMALDI DONAHUE

89

Visiting a Strangely Familiar Country: Writing in Another Language

ERNESTO LIVORNI

99

Selected Poetry

MONICA GUERRA

113

Magarian’s Poetic Beasts

ANDREA SIROTTI

119

Selected Poetry

BARET MAGARIAN

131

Innovation and Invention in “Kidhood”: When a Poet Writes in a Different Language

AL REMPEL

139

Selected Poetry

SANDRO PECCHIARI

155

Brenda Porster: The Body as Home, the Home as World

ALESSANDRO CANZIAN

163

Selected Poetry

BRENDA PORSTER

179

The Immense Structure of Happiness: Rachel Slade and the Metamorphical Poetry of Apocryphal House

LOREDANA MAGAZZENI

185

Selected Poetry

RACHEL SLADE

Introduction: Transnational Italian Poetry

Alessandro Canzian, Simona Wright

Literature, and poetry in particular, has always been a tool to understand culture. Sometimes it has even gone beyond and helped cultures to expand and develop. Poets understand that language, essential to human survival, has its own limits, but they also see these limits as an incentive to produce new expressive forms, other languages that transcend the old one to understand and tell what is not yet immediately comprehensible or immediately utterable. This awareness, coupled with the desire to trespass the limits of one’s language, have produced what we today call literature.

Language, intended as an instrument that offers the word countless opportunities, requires nevertheless a corollary of skills. Using it in a poetic way requires a certain familiarity with literature, or rather with literatures, with the oral and written traditions that preceded it, formed it, and complicated it. Language is therefore bound by the vast experience of the past. Italian, a language with a time-honored literary tradition, offers an exceptionally interesting case. On the one side, it boasts the legacy of its noble past, and contemporary poets frequently return to the classics to draw inspiration and new meaning. On the other, that same legacy becomes a burden that crushes the emerging voice under the immense weight of its greatness. This contradiction has produced different reactions, driving poets to experimentations that were considered at times reactionary or decadent by later authors, but which nonetheless have impacted the literary movements of twentieth-century Italian letters.

In the second part of the twentieth century, after the tragic experiences of fascism and WWII, the economic boom, the years of terrorism, the hedonism of the eighties, and the economic and political crises Italians experienced in the new millennium have exacerbated what Pier Paolo Pasolini defined as Italy’s “anthropological mutation.” The value he found in cultural and linguistic authenticity had been rejected while consumerism had deprived the new generations of the utopian dynamism that usually characterizes them. The great dreams that animated political and social movements in the sixties and seventies was extinguished, yielding a widespread sense of disenchantment and frustration. From the nineties, the ethical drift caused the rejection of every sense of civic responsibility while politics was bent to serve exclusively individual interests and personal agendas. Italy’s cultural and social crisis was central to the poetry of the period and testified inexorable ruin often more effectively than narrative production ever could.

[…]

The editors of this volume are aware of the experimental and provisional critical approach utilized in this project, but wanted nevertheless to start a conversation on the possibilities offered by the complexities of our reality as they are witnessed, recorded, and experienced by Italian and Italophone poets today. We hope to have started a productive conversation that may help Italian and Italophone authors to develop their poetic expression further and we invite critics to articulate their own perspectives on this emerging phenomenon. Globalization informs our lives, often in a negative way. We hope that this exploratory volume inaugurates a debate on the expressive possibilities of the countless transnational encounters in which we dwell every day, at both the linguistic and the cultural level. Most of all, we hope that the rich complexity of these encounters can be translated in new and original poetic forms.

Translingual Peripheries: Ilaria Boffa’s Practice of Everyday Poetry

Simona Wright

Ilaria Boffa was born in Italy in 1972 and lives in Padua. She has a degree in Economics and works for an international non-profit organization. A prose writer for years, only at the age of thirty-eight did Boffa start to write poetry, when she felt the need to create a personal space of expression, a metaphorical non-lieu that allowed her to give form to her multi-sensorial, corporeal subjectivity. Her poems were published in two anthologies, Glocalizzati (deComporre Edizioni, 2014) and Viaggi DiVersi (Elio Pecora, 2013) and unpublished work appears in online journals (Atelieronline, 2017). She has published two volumes of poetry in English, Spaces (Limina Mentis, 2015) and The Bliss of Hush and Wires/Periferie (Samuele Editore, 2016). A selection of poems written between 2010 and 2014, Spaces explores both the poet’s physical and emotive reality in a rough and even tentative way. Driven by a marked experimental tension, Boffa’s first collection attempts to freely link form and image without the limitations perceived in her own linguistic background. The choice of English is, for this exophonic poet, original and significant, nervously folding challenges with possibilities. In the postcolonial, transnational realities we inhabit, authors who choose a different language for their literary work are an ever-growing flock. They come to this decision for various reasons, most commonly after a personal experience of displacement, dislocation, or migration, and with various degrees of ambivalence, discomfort, or hopeful anticipation.

[…]

A restless inquisitiveness marks Boffa’s authorial voice and her upcoming poetic collection, A Million Sounds (Samuele Editore, 2019), provides further evidence of her interest in experimentation. A project based on the notion of ‘field recording’ allows Boffa to explore the fields of eco-poetry and eco-poetics and to test her verses against issues such as globalization and global warming. Driven by her natural interest for the combination of human voice and urban soundscapes, Boffa has started to collaborate with international avant-garde musicians, recording her poems over their instrumental pieces to produce an originally innovative multisensorial approach to the poetic experience (Ilaria Boffa and Lucien Moreau, 2018). The pursuit of marginal sounds and the symbiosis with peripheral artists open up new spaces for the representation of the quotidian, whose architecture forms the background for the poet’s visions, images, and rhythms. Boffa links “Concrete (visual) poetry” and “space poetry” with the measure of music to invite us to reflect on our post-human way of life, and to re-think our physical and emotional relationship with the natural environment.

ILARIA BOFFA

The Distance

I.

There’s a distance that cannot be covered.

The journey appears circular, a repetition

of the night and its perimeter.

When a dog runs, it does not look behind,

there’s no measure of its own being.

Retrievers know how to please their master.

But linden trees soothe each frail creature. Step by step

over the meadow, the look crosses corn fields.

A fallow land will bring silence.

II.

Far, too far, continents

burn in the distance, attracted by gravity

and the beloved soil.

That line of melancholy rends the soul

like a sharp thread.

Where’s patience that is supposed to be embraced?

Waiting is our mutual gift.

A Strange Geometry

Victor Xavier Zarour Zarzar

Moira Egan is an award-winning poet from Baltimore, Maryland. After earning her BA from Bryn Mawr College, she went on to complete an MA from John Hopkins University and an MFA from Columbia University, where her graduate manuscript was selected by James Merrill for the David Craig Austin Prize. Egan’s first collection of poems, Cleave, appeared in 2004. Since then, Egan has published Bar Napkin Sonnets (2009), winner of the 2008 Ledge Poetry Chapbook Competition, Spin (2010), Hot Flash Sonnets (2013), and, most recently, Synæsthesium (2017), which earned her The New Criterion Poetry Prize. Egan is also the editor, along with Clarinda Harriss, of Hot Sonnets, an anthology that attests to her lifelong dedication to poetic form. Before moving to Italy in 2007, Egan lived in the United Stated and Greece. Now, she resides in Rome with her husband and co-translator, Damiano Abeni, and their cat Isis. Egan and Abeni’s collaborative work is well-known; together, they have translated over a dozen volumes of poetry by authors such as Mark Strand, John Ashbery, and Charles Simic. In addition, the couple has published three bilingual collections of Egan’s poetry: La Seta della Cravata / The Silk of the Tie (2009), Botanica Arcana / Strange Botany (2014), and Olfactorium (2018). In the past, Egan has had residencies at the James Merrill House, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the Virginia Center for Creative Arts, among others. Currently, she teaches Creative Writing at St. Stephen’s School. Thriving in the tension between reverence and irreverence to tradition, Egan’s work infuses new life into poetic forms that contemporary poetry has tended to regard as antiquated—proving that forms like the sonnet are not only alive and well but might also be the perfect conduit to express the tension of modernity.

[…]

Unsurprisingly, these tensions remain unresolved, and we are left with a sort of in-betweenness. A precarity, both of desire and of the textual body, the in-betweenness of punctuation and prepositions. Much as the prepositional stanza of “Circe Offers Comfort” is suspended between past and present, Egan’s speakers are caught in the tension between, on the one hand, the experiences and emotions that have formed them and shaped their desires, and, on the other, their perception of the world as dictated by these desires. At play is also a manifest generic in-betweenness—tradition invoked only to be estranged. And then there is the tension dictating the poetic production itself: the tension of a poetry written in English yet originating in Italian soil; a poetry that dramatizes the play between the centrifugal forces of emotion and the centripetal power of form; a poetry produced by a mind deeply versed in diverse linguistic traditions, and, as such, capable of distancing itself from the English language; a poetry, finally, created with the expectation of translation. It is these tensions that make Egan’s poetry utterly contemporary and allow it to speak to the “uprootedness” of our modern selves, at home nowhere, yet everywhere.

MOIRA EGAN

Seven

Consider the dumb beast Lust,

how she lumbers in, uninvited

unintentional,

busts up the crystal stemware,

leaves your candles burning all

night, rips your best negligee

in the most neglectful way

as if you hadn’t spent a

hundred bucks on it. As if

she has a place in your bedroom,

your heart, some argument

you lost like a poker game,

all the while never cracking

a smile. Or consider this:

that she is fine and wily

as the leopardess Dante

beholds in the first Canto,

her coat dappled dark and light

like sin and salvation in

the same bated breath. What if

she is sleek and smart as a

red-winged hawk, eye unerring

for the prey, the goal, the gold

that glints and glitters its sign,

Noli me tangere, don’t

touch. But you will, of course, it’s

your nature to want what’s not yours.

The fetters fall, sad and pure.

Circe Offers Comfort

The cyclicality of history

has traced this circle, strange geometry,

in which Odysseus forsakes his bed

and wanders back to Circe’s isle instead.

I am the Circe, then, whose father left

the little girl behind, mother bereft.

I saw my parents’ bed uprooted long

before that other woman came along.

My family called her “whore” or sometimes “bitch.”

Meanwhile I learned my trade: a little witch

who grew into this woman whom you love,

whose incantations you’re enamored of.

(That preposition never suited me.

I never wanted of; I liked between.)

Now I’m the whore or bitch of whom they’ll speak.

We know the truth; I’ll turn my other cheek

and try to love you, best I can. It’s chance

that brought us here, and all the potions, chants

a witch can summon up can only calm

a little while. Smoothed into you like balm,

I’ll feed you food and watch you sleep. The dreams

will fade, although I know for now it seems

her name will haunt you like a childhood verse.

To walk away’s both blessing and a curse.

The Depths of Love and Sorrow in Allison Grimaldi Donahue’s Poetry

Cristina Perissinotto

Allison Grimaldi Donahue sounds the depths of love and sorrow with an economical language that is akin to some Italian hermetic authors of the twentieth century, with whom she is undoubtedly familiar. Her poetic production is directly influenced by the work of Robert Creeley and Eileen Myles (Grimaldi Donahue, “Attendiamo”), as well as by the poetry of Vito Bonito, which she also translated. The present essay explores Grimaldi Donahue’s poetic production in light of the Italian poetic tradition and of ancient and early modern suggestions. Although Allison Grimaldi Donahue is mired in postmodern and confessional poetry, she shows modes and stylistic features that remind one of the poetic canon of the Italian tradition.

[…]

Unlike the enumerative technique present in Montale’s poem, in Grimaldi Donahue the images are nesting into one another, which may be a reminder of the elusiveness of the image of the beloved, after her passing. The couch hides and then reveals a Polaroid, which portrays a dog, who is leaning on the legs of the person whose presence is still so strongly felt. All those aspects—couch, polaroid, dog and legs remind one of the absence that the author is mourning.

[…]

The literature and criticism on the value of dreams in poetry and prose is large. From Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis onwards, literary dreams have often been a source of knowledge as well as a way to find solace from daily life. In this dream, the scene is peaceful and bucolic, and the reader no longer expects an absence, since the beloved is present with the author. In a way, the circle is complete— the author is included, and the lack of a bridge highlights the sense of hortus conclusus, an enclosed garden separated from real life.

Grimaldi Donahue’s poetry is surprising this way. It works through mourning and loss, though the pain of love without a beloved, and offers, its own minor consolation. Even though such offering comes in sparing, precise language, it hints at a long tradition of poets and writers before her, who found consolation in the written word.

ALLISON GRIMALDI DONAHUE

found a polaroid of the dog

on the couch the summer

before you died

those are your legs

the dog lies on

no human face only human legs

immobile dualistic

the mind already gone to some other place

sometimes i run my index finger over my thumbnail

to feel the anemic bumps—

though nothing compared

to your nails

i am able to convince

myself for a second that i am holding

your hand

horses always appear in

the rain

chewing grass

through fog

next to old silos

old caves

old bones

in switzerland

the mountains here

are not green

if you, pile of dust

could accumulate

what kind of being

would you be

Visiting a Strangely Familiar Country: Writing in Another Language

Ernesto Livorni

The language in which a poet writes offers a different set of complications, assuming that we can limit that language to English, French, and Spanish. In the Italian context, Italian poets most often consciously adopt the English language to write their poetry, while also writing their poetry in Italian. There are at least a couple of questions that the critic would immediately ask. Is the poetry written in either language and, if so, why is that the case? According to which criteria is one language chosen over the other? When the poetry is written in a poet’s native language, is the poet offering a translation of their poems from Italian into English? Writing in a different language does not eliminate either possibility and the consequential ambiguity in the poetic operation that the critic must interpret. That ambiguity may often be solved thanks to specific information on the poets, their biographies, life and professional experiences, ideologies, writing objectives.

This information is partially relevant in understanding the reasons why Monica Guerra started writing poetry in English, after she had already been writing poetry in Italian. After publishing an intriguing essay (Il respiro dei luoghi, 2014), which is a dialogue with the sociologist Daniele Callini, Guerra published two collections of poems in Italian (Sotto di Sé, 2015; Sotto Vuoto, 2016), before releasing the collection Sulla Soglia (On the Threshold, 2017), which contains poems in Italian with English translation. To be sure, besides the assumption that Monica Guerra is a native speaker of Italian writing poetry in English as well and that the order of the languages in the title itself speaks to Italian’s status as original, there is another puzzling suggestion that invites us to consider that Monica Guerra’s poetry may have been written in English and translated into Italian. Indeed, the English version of the poems appears on the left page, whereas the Italian version appears on the right page. Although the potential causality of the order of the two languages cannot be discarded, the effect is that of conveying a certain order of composition to the reader, as the left page traditionally hosts the original version of the poems, relegating translations to the right page.

[…]

The attempt at writing poetry in a foreign language is a daring one, in which the cultural background and the poetic tenets of the writer meet first the constraints of the language and then the history of poetry writing in that language. Monica Guerra remains faithful to her poetics, one that seems to have much in common with the early twentieth-century literary tradition of Italian hermetic poetry. In that respect, the English-speaking reader may be encouraged to retrieve the corresponding trends in the poetry written in that language according to a style and a mode that privileges chiseled lines aiming at enlightening moments of insight.

MONICA GUERRA

expectations

(Texas, July 2017)

cruel and reddish air

always craving the rain

while slow lying stones

stir the water’s faults

a precarious silence floats

this is the fraud

the green desert the expectations

always near but then

they never happen

the harsh voice of vastness

stings in the moist under the skin

and a peaceful concern

floods the silence’s fault

how easy it is alone

the other eye of the moon

the desert

and how difficult it is

a cursory peace

among squirrels’ fingers

and concrete, giving up

is a wild green

fast setting

a mumbled melancholy

but you, unroll your lashes

ruffle the virgin nests

among your hair on your breasts

in a deserted den

truth trembles free

Magarian’s Poetic Beasts

Andrea Sirotti

Baret Magarian is an Anglo-Armenian poet and writer, born in London, now resident in Italy, in Florence. An idealistic and charismatic author with a growing following of admirers, appreciated for his brilliant public readings, he has published poems and works of fiction in magazines and with independent publishers, both in English and in Italian translation. His novel The Fabrications, published in the United States, was hailed by The Times Literary Supplement, Kirkus Reviews, and The New Statesman as a work of considerable literary value. A collection of his short stories, Melting Point, which confront with daring virtuosity many kinds of short fiction, was brought out by the Italian publishing house Quarup. He recently published a bilingual edition of his poetry with the Roman publisher Ensemble—Scherzando con tutte le mie bestie preferite—which displays the full flowering of his poetic voice and the range of his poetic interests. The book was enthusiastically acclaimed by Corriere Fiorentino, and the Italian critic Simone Innocenti and the British novelist Jonathan Coe have both compared Magarian to great masters of 20th-century literature. Some of his texts have been successfully adapted for the theatre. He is also active as an amateur painter and pianistcomposer.

His multi-faceted production revolves around some common characteristics: the unshakeable conviction that literature plays an ethical role in society, the irreverent re-reading of literary forms and genres, and the sometimes painful analysis of the weaknesses and the distortions of social life. Poetry, within Magarian’s wider and markedly eclectic output, plays a central and tangential role at the same time. Central because for him poetry is the most extreme form of writing and literary militancy, tangential because it touches and influences other forms of artistic expression, contaminating them without being incorporated, remaining eminently lyrical and, in a sense, elitist. Poetry is a pure and niche genre, which stands apart, untouched by fashions and trends.

[…]

Writers, as Magarian likes to say, should be like children. Spontaneous and innocent, they should discover the world as if for the first time: “I’ve learned from children in their haystacked bliss” (“If you came to me. 3” 134). And discovering the world, to note with disappointment that so much is wrong, that the king is naked, and that men stubbornly walk the wrong pathways (see the apologue “The Way of Life”). And then the poet, like an irreverent but empathetic picaro, proud of his marginality, raises his voice, in an enterprise that has something colossal about it, an unrealistic and anachronistic task doomed to failure. A task that appears to us now as urgent as at no other time, even if remains unattainable.

BARET MAGARIAN

Can I stay with you

Can I stay with you just a little while

To take the pressure off

To put my feet up

To have a smoke, a drink with you

To loosen that corrugated noose round the world’s neck

To elongate the glimmers of light sequestered into

Far flung corners of the shattered globe?

Could I stay with you just a little bit longer

Could you teach me to dance, tremble

In the eclipse between life and death?

Can I stop with you a while,

Before I don my armour again with etiolated limbs

Before I go out again into the war zone the interplanetary banshees

The flickering whips twitching the world’s horizon of pain

Can I stay with you just for a little while longer?

I’ve spoken with seas and tides, been privy to the secrets of storms

Exchanged pleasantries with time, wrestled with the wind

Wondered among stars and planets, and seen the old blue earth from

afar

I’ve plunged into electric tides and felt the current of the universe

Plugged into the live circuitry of my form, I’ve been a Grecian urn,

A supine statue, a whirlwind, been spewed out and ejected

As though from the shaft of an active volcano

But I’m back, I lived to tell my tale, I’ve come to

Drink a toast with you, to marinate your limbs with pleasure,

And to bathe you, dress you, baptise you,

I’m still alive, I’m still here, I can be servant to your master,

The oriental spice that has no name, that travellers have searched for

in vain,

I can be your flame, torch, sunray, enchantment, the lament

Of the desert wind, the river’s slow motion once more after the

eternal winter’s cessation

I can be all this, and so much more, if you’d only let me reach you

But you sit, slow and furrowed, with a dark brow, you have reached

A staleness, a stillness, you are like some great bear in its cave

Innovation and Invention in “Kidhood”: When a Poet Writes in a Different Language

Al Rempel

Sandro Pecchiari has published four poetry books with the Italian publisher Samuele Editore: Verdi anni (Years Can Always Turn Green), 2012; Le svelte radici (Uprooted and Rerooted), 2013; L’imperfezione del diluvio – An Unrehearsed Flood, bilingual version, 2015; and Scripta non manent (Written Words Never Remain), 2018. Some of his works have been translated into Albanian, English, French, Spanish, and Slovene in several different anthologies and his poetry has been reviewed many times. With Alessandro Canzian and Federico Rossignoli, he organizes fortnightly poetry meetings named La Scontrosa Grazia at the bookstore TS360, Triest, Italy. He has also collaborated with the Italian literary magazines Traduzionetradizione (Milan) and L’Almanacco del Ramo d’Oro (Trieste).

Pecchiari writes poetry in Italian, his mother tongue, as well as in English, and he has also translated English poetry into Italian and from Italian into English. The many themes in his writing include the intersections between his past and his present life, loss and hope, foreign lands and finding home, and between the known self and yetundiscovered self. Pecchiari writes in an open, free verse style that moves fluidly between images and events, and the poet’s commentary on them. His lines are generally compact and forceful, and in a stream-of-consciousness style, which reinforces the feelings and emotions he is trying to convey.

When a poet writes in a language other than their mother tongue, it forces innovation and invention that would not necessarily occur to a native-speaking poet, whether it is because the poet attempts to describe something he does not have words for, or— consciously or unconsciously—translates ideas or turns of phrase from his mother tongue, or simply discovers new constructions by happy accident. Pecchiari’s poetry in “Kidhood,” a poem in thirteen parts about growing up as a farm boy in the aftermath of the Second World War, is replete with such invention. The poem also explores where language comes from, in the context of the ironies and contradictions of war, as well as within the setting of a coming of age story, where boy becomes man, and where manhood is not defined in a heteronormative sense, over and against the “manliness” of soldiers.

[…]

The journey of poetic discovery is never about being absolutely certain, it requires a humility that comes from the understanding that language cannot describe one’s experiences or observations precisely, and this openness allows for a greater interplay between cultures and nations. Poetry can break down barriers and walls and poems can be the first diplomats to enter across the border, carrying new understandings and new ways of seeing the world.

SANDRO PECCHIARI

KIDHOOD

1.

We sucked from udders,

hiding friendship in the cowsheds

wearing it like drops of white mulberries

on our lips, not showing off.

The river at the wind was our fence,

the fence a border

to foreign kids and fights –

at times we crossed at fords to barter

for long reeds or fish,

lending our own world

borrowing words or weapons.

Ditches dug around our houses,

doubled summer

huge unending clouds –

our wilderness drowned in buckets

of sun-warmed water

– left out all afternoon –

to wash away our mud,

to wash us back

into a world of order.

2.

our questions hushed

into days of mallow buds and berries:

the world was food for us.

our time spurred a new language of nettles,

against our skins

scattered scraps of words

open-hand sore pricking

cicadas spoke for us.

Brenda Porster: The Body as Home, the Home as World

Alessandro Canzian

[…]

Porster’s interest in poetry started at an early age. During her university experience, however, her work was harshly criticized, producing a mental block that lasted until she moved to Italy, where she experienced a sort of “Renaissance” and returned to write verses. Her new cultural location would soon determine her linguistic choice, but in the first years her poetic voice lingered in a sort of cultural limbo, struggling to find a new subjectivity. The first poems were written in English, attesting to the persistence of her native cultural background but also isolating the poet from the Italian speaking literary circles. The participation in a “Laboratorio di scrittura” (creative language course), was instrumental in giving Porster the support to adopt her new language, Italian. Soon thereafter, she joined “La Compagnia delle poete,” a group of transnational female poets who had decided to write in Italian and perform their work on national and international stages.

The double literary identity so successfully embraced by Porster is reflected in the images she has chosen to define her new linguistic location. Talking about Italian as her new “home,” she indicates that languages are communities of loved ones sharing the same humanity and ethical values. Social and political commitment remain fundamental in Porster’s work, and she has recurrently criticized the US government for its insatiable appetite for global hegemony. Her migratory experience has led her to understand history as a series of personal experiences that form us as individuals and citizens. Space remains the key element of her poetic work, where it appears as places, events, and belongings that transform the self in a more open and welcoming sensitivity. It is in these terms that we can understand Porster’s work as an expression of her double identity as a writer and as a migrant, where her journey into another language signifies the opening of a new universe of imagination and creativity. Her experience epitomizes that of a wanderer, whose desire to know and understand the world around her never ceases to reveal the inhumanity, suffering, and loss which characterizes it. In her poems, we often encounter tragic figures, like this modern Antigone, a Rom mother arrested and charged with illicit concealment of a corpse “for burying her baby daughter on the beach of Apulia, where she had landed after escaping from Kosovo.”

[…]

BRENDA PORSTER

Antigone in Apulia – A Gypsy Mother’s Tale

Cast out we were

into the dark sailing away

not towards, but together,

she exactly filled

the empty cradle of my arm

a damp-warm weight her need only I

could meet, the dark vague depths

of eyes, the desperate searching,

the shell-clenched fists rosy

uncurling prawns grasping

my breast, tentative

lips and then that clamping pull

of life from me to her fulfilled

our mutual need, each to each

bound, in perfection,

the circle closed.

When did I see she was not

there, her small weight gone

limp, suspended, all warmth

drained, the searching ended?

She no longer needed

me, while I was left, longing

and my arm circling

empty. Chill terror clamped

my breast and suddenly I knew:

they would come and

cast her down to depths

infinite she would drop

down never to be found,

her tiny body unfurling

waving anemone limbs

forever searching forever

exposed.

No! This could not be! I,

her mother, would provide

for her a warm covering, decent sand

and place, a collocation

of the mind, for both our needs, together

a final time, before I said

once more: good-night,

good-night, my heart’s own dear,

and left her there.

Note: For burying her baby daughter on the beach of Apulia, where she had landed after escaping from Kosovo, this Roma mother was arrested by the Italian police and charged with illicit concealment of a corpse

The Immense Structure of Happiness: Rachel Slade and the Metamorphical Poetry of Apocryphal House

Loredana Magazzeni

Rachel Slade’s poetry relates to the contemporary human condition, to feelings of nomadism, alienation, and acceptance of what is unknown and disturbing.

Born in Putnam, Connecticut, she currently lives in Italy. Her principal activity is as a painter. Her most recent exhibitions are Citizenship (Villa Corrier-Dolfin, Porcia, PN, 2014, with the presentation of Alessandra Santin), Crambe Tataria (Villa Cattaneo, San Quirino, PN, 2015, with an introduction by Carlo Vidoni), Ephemeral (Teatro Russolo, Portogruaro, on the occasion of the Cinderella show of Sergei Prokofiev), La casa apocrifa (Cantine Collalto, Susegana TV), Devota come un ramo (Maniago, PN). For Samuele Editore she oversaw the presentation of several poets in the New York City Poetry Festival of 2014 and several book covers (including most recently: Periferie/The Bliss of Hush and Wires, by Ilaria Boffa, and Nuviçute mê e sûr, by Stefano Montello). Apocryphal House/La casa apocrifa (2016) is a plaquette that serves as prelude for her debut book released in 2018.

The title of her poetic collection itself, Apocryphal House, refers to apocryphal texts, works of doubtful authorship or authenticity, a reference which only adds to the feeling of distance and estrangement. Like her pictorial production, Slade’s poetry seems full of vivid, almost tangible imagery that shapes mysterious worlds and paves the way for new beginnings and possibilities, just as roots can sprout into plants.

In Slade’s style, words can be compared to real-life embryos and cells, pushing to break through the page and find new boundaries. Slade’s writing is like raw material to be molded, like the porous colors she draws with: her words grow denser to eventually create a painting of the outside world. Recurring patterns and a sense of ritual pervade the style of the poet, whose personal beliefs are only hinted at.

[…]

In Slade, word and material merge, finding their strongest thematic features in ambiguity and the impossibility of a univocal vocation, which lend them their evocative mystery.

An art and a poetry, finally, created to work together, and to be found from the lector with a particular disposition to listen and recreate worlds. In this sensibility of mind, Slade’s poetry bursts forth deeply modern and sincere, that translates the contemporary themes, lessons, and passions of our day. She writes and speaks of contemporary arts with a female disposition to hospitality moving from her own experiences of nomadism, estrangement, and cosmopolitism.

RACHEL SLADE

Pillar

what letter begins your country’s name

how shall we begin to make something whole again.

how shall we name the body.

its rivers and roads.

my companion folds herself into sleep.

I ask.

how shall we name the fields

where we were abandoned

like nightgowns.

and I ask.

how shall we name the beginning of the stone

used to martyr the bird

or the blue wing of solitude.

I ask.

how to beat the names black.

how to die like a column of numbers.

I ask. though she sleeps.

how to name the honey in the mouth.

the body of my body, sex of my sex.

the patron saint of empty houses.

Iris

1.

mine is the language of standing still

a snail dreaming on a pillow of eggs

small numbers, a column of fixed resin

this is the territory of shaken stars

mine is the language of matrimony, the firm agreement

of four feet in river water, my name a stone thrown at the sky

my hesitation is the outcry of wooden horses

my death is a horse laying down in the water

its ribs the archway of earth’s desire

instinct and calculation made plastic and real.

an endless land of white stone. immense and strategic.

I am an island of snow and things fallen asleep in the snow.

I am a land without sorrow.